Bad World War II analogies appear to have become a dime a dozen in today’s political discourse. In just the past few months, I’ve excoriated Russell Moore for his ridiculous reference to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in response to President Donald Trump’s push toward a peaceful resolution of the war in Ukraine and pilloried Max Boot’s baffling comparison of Ukraine’s recent attack on Russia’s bomber fleet to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

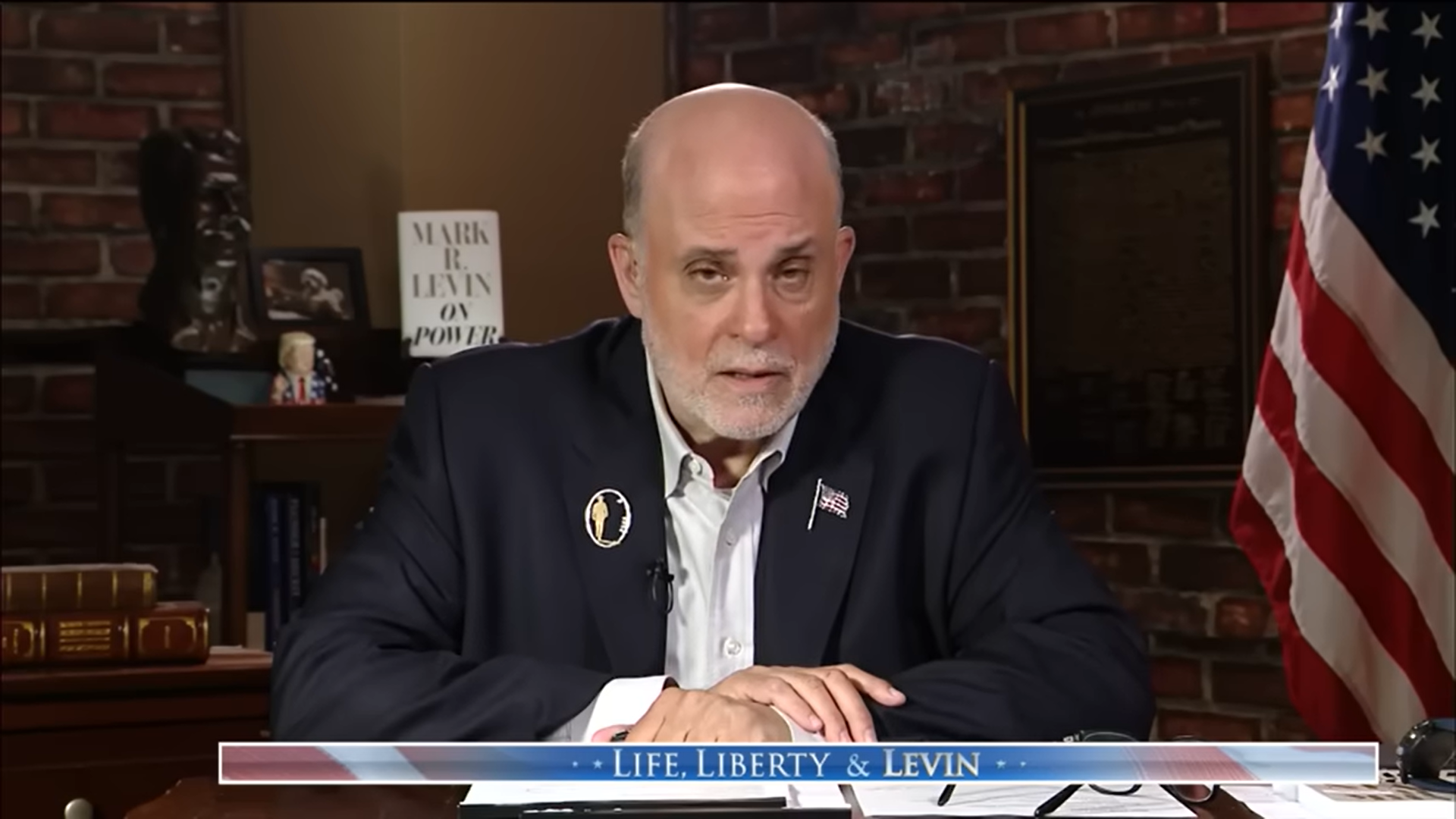

Now, Mark Levin, in his zealous crusade to push the United States into directly joining Israel’s strikes against Iran, has invoked the most tired and most misconstrued talking point related to the Second World War: appeasement.

Levin’s screed (it’s far too light on substance to be called an op-ed), titled “Isolationism is the same as appeasement — and it’s keeping Trump, Netanyahu from transforming the Middle East,” does little more than launch ad hominem attacks and provide a masterclass in projection. It’s amazing to read sentences like these: “They’re too self-righteous in their ignorance to realize how absurd they sound. … In fact, they’re so blind and self-important that they don’t see the new foreign policy taking place in real time, right in front of their eyes!” and not even detect even a hint of self-awareness from a man who is advocating for the United States to become stuck in yet another Middle East quagmire.

Remember how all those other times our attempts to “transform” the Muslim world worked out so well?

Afraid that his readers won’t be convinced by merely insulting the intelligence of so-called “isolationists,” Levin tries to morally blackmail any potential skeptics by blowing the appeasement dog whistle as loudly as he can. “There’s nothing new or good about isolationism, which, in a word, is appeasement. It’s old and promotes war, such as World War II,” he writes bluntly.

It seems like whenever very reasonable people object to yet another forever war, neocons crawl out of the woodwork to screech “appeasement!” to try to cow their foreign policy opponents into embarrassed silence. If you don’t agree with the neocons’ next regime-change project, you’re no better than British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who meekly gave in to Adolf Hitler in 1938 and emboldened Nazi aggression — thereby unleashing all of the devastation that ravaged Europe. If you don’t believe in toppling tinpot dictator No. 12, installing an American puppet state, and sacrificing untold amounts of American blood and treasure, you, specifically, are setting the stage for another World War II, another Holocaust. At least, that’s the implication.

In other words, accusing someone of appeasement is intended to bestow a black mark on him, branding him as a spineless, overly naive stooge. When they’re not comparing him to Hitler, Democrats love to accuse Trump of appeasement — mostly toward Vladimir Putin. Framing Putin’s Russia as a Nazi-like regime poised to thunder across all of Europe has been a critical talking point for those who wish to see us more directly embroiled in the Russo-Ukrainian War.

It’s ridiculous on its face to say that isolationism is the same as appeasement — otherwise we’d have to involve ourselves in every single conflict and dispute on the planet (oops, too late) or else we’re “appeasing” someone. The continued usage of appeasement as a political cudgel, however, shows that neocons like Levin don’t know the logical reasons why the Western Allies pursued a policy of appeasement in the years leading up to World War II.

The most infamous act of appeasement in the lead-up to World War II was the Munich Agreement. After the Anschluss with Austria in March 1938, Hitler turned his gaze toward the Sudetenland, a strip of land in Czechoslovakia that bordered Germany and was mostly inhabited by ethnic Germans. He demanded the territory and threatened war.

The leaders of Britain, France, Italy, and Germany met in Munich and signed the Munich Agreement on September 30, 1938. Hitler was allowed to occupy the Sudetenland in exchange for a promise to respect Czechoslovakia’s new borders. Only a few months later, in March 1939, German troops moved into the rest of Czechoslovakia, violating the Munich Agreement.

The German betrayal after Munich galvanized the Allies and inspired Poland to refuse Hitler’s demands for territorial concessions, and World War II began on September 1, 1939, with Germany’s invasion of Poland.

With the benefit of hindsight, the Munich Agreement appears to be an unforgivable blunder on the part of the Western Allies. They had given Hitler valuable territory and fatally weakened a potential Eastern European ally, all for what turned out to be an empty promise. Historians, politicians, and commentators have railed against it over the past 80 years, heaping particular scorn on Chamberlain’s proclamation of “peace in our time” in the aftermath of the agreement.

Britain and France wanted to avoid a war in 1938 for two very important reasons. First, Chamberlain and his French counterpart, Édouard Daladier, were not naive. In fact, they were acutely aware of how devastating another European war would be. Britain and France believed that a war with Germany would benefit the United States and the Soviet Union at the expense of the traditionally dominant Western European powers. Daladier said that another war on the scale of World War I in Western Europe would mean the “utter destruction of European civilization” and that such a war would allow the Soviet Union to become the hegemonic power in Europe.

Britain and France expected to win a war against Germany, but they also knew that their international positions would be weakened by such a war. So looking at the bigger picture and the likely long-term effects, they wanted to try to avoid a war if they could. Who would primarily benefit from another American adventure in the Middle East? It’s undoubtedly communist China. With American attention, money, and military equipment once again focused on the Middle East, China could easily exploit that to increase its own power in Asia, Africa, and the rest of the globe.

Second, though Britain and France believed that they would defeat Germany, they also recognized that Germany’s rapid rearmament had allowed it to reach a state where it could have a chance in a future war. In preparation for what they predicted would be another long, bloody struggle like World War I had been, the Allies began their own program of rearmament. In fact, both Britain and France had stepped up their military spending before the Sudetenland crisis. Daladier’s government pushed to double France’s military budget in anticipation of a confrontation with Germany, while Britain embarked on a massive expansion of the Royal Air Force.

If war was going to come, Britain and France knew that the longer they delayed it, the better position they’d be in. Germany’s resources, infrastructure, and industrial base were extremely strained by its own military buildup, and it couldn’t sustain its breakneck pace without risking an economic crisis. Meanwhile, the Allies would have eventually won the arms race by ramping up their own production and procuring equipment from the United States.

Hitler was keenly aware of this fact, and it was one of the principal reasons he decided to launch the war in 1939: He knew that Germany’s advantages in equipment production were shrinking year by year because of Allied rearmament. If he didn’t launch a war soon, the Allies would be too well prepared and too well equipped for Germany to have a realistic chance of winning. One of Hitler’s closest confidants, Albert Speer, said Hitler believed that Germany’s “proportional superiority” would “constantly diminish” vis à vis the Western Allies after 1940 if a war did not break out before then.

“Because of our restrictions our economic situation is such that we can only hold out for a few more years. … We must act,” Hitler said in an August 1939 address to German military commanders.

So appeasement was not the epitome of moral cowardice that neocons like to pretend it was. It was a shrewd, if somewhat cynical, bit of political calculus. If it really did help avoid a war with Germany, that would help maintain Britain and France’s position as the two top European powers. If it didn’t, the longer the Western Allies could delay a war, the more advantages they would have if and when one broke out.

Accusing people of appeasement and comparing them to Neville Chamberlain just because they don’t want the United States to rush headlong into another international conflict is a tired and ahistorical trope. It’s not only a far too simplistic take on the events leading up to World War II, but it’s also one that’s dishonestly used to shame perfectly rational people into a potentially disastrous course of action. A string of bombed-out and ruined Middle East countries shows us the catastrophic results of heeding neocons’ hysterical warmongering. If they get their way, there really won’t be peace in our time.

Hayden Daniel is a staff editor at The Federalist. He previously worked as an editor at The Daily Wire and as deputy editor/opinion editor at The Daily Caller. He received his B.A. in European History from Washington and Lee University with minors in Philosophy and Classics. Follow him on Twitter at @HaydenWDaniel